What Regulatory Commission Has Control Over T.v. And Radio?

The Federal Radio Commission (FRC) was a government bureau that regulated United States radio communication from its cosmos in 1927 until 1934, when it was succeeded past the Federal Communications Committee (FCC). The FRC was established by the Radio Act of 1927,[i] which replaced the Radio Act of 1912 later on the before law was found to lack sufficient oversight provisions, specially for regulating broadcasting stations. In addition to increased regulatory powers, the FRC introduced the standard that, in order to receive a license, a radio station had to be shown to be "in the public interest, convenience, or necessity".

| |

| Agency overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | 1927 |

| Dissolved | 1934 |

| Superseding agency |

|

| Jurisdiction | Us Federal Government |

Previous regulation [edit]

Radio Act of 1912 [edit]

Although radio advice (originally known every bit "wireless telegraphy") was developed in the tardily 1890s, it was largely unregulated in the The states until the passage of the Radio Deed of 1912. This law prepare up procedures for the Department of Commerce to license radio transmitters, which initially consisted primarily of maritime and apprentice stations. The broadcasting of news and entertainment to the general public, which began to be developed early 1920s, was not foreseen by this legislation.[2]

The first Commerce Section regulations specifically addressing dissemination were adopted on December 1, 1921, when two wavelengths were gear up aside for stations making broadcasts intended for a general audience: 360 meters (833 kHz) for "entertainment", and 485 meters (619 kHz) for "market place and weather reports".[3] The number of broadcasting stations grew tremendously in 1922, numbering over 500 in the Us by the end of the year. The number of reserved transmitting frequencies also expanded, and by 1925, the "circulate band" consisted of the frequencies from 550 kHz to 1500 kHz, in ten kHz steps.

Herbert Hoover became the Secretary of Commerce in March 1921, and thus causeless main responsibility for shaping radio broadcasting during its earliest days, which was a difficult task in a fast-irresolute environment. To aid decision-making, he sponsored a series of four national conferences from 1922 to 1925, where invited manufacture leaders participated in setting standards for radio in general.

Legal challenges [edit]

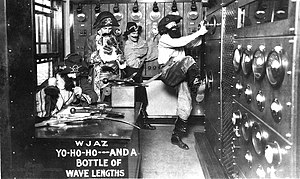

In 1926, station WJAZ successfully challenged the authorities's authority to assign transmitting frequencies under the Radio Act of 1912.[four]

During his tenure Hoover was aware that some of his deportment were on shaky legal ground, given the limited powers assigned to him past the 1912 Act. In particular, in 1921 the department had tried to decline to issue a renewal license to a point-to-point radiotelegraph station in New York City, operated past the Intercity Radio Company, on the grounds that information technology was causing excessive interference to before radiotelegraph stations operating nearby. Intercity appealed, and in 1923 the Court of Appeals of the Commune of Columbia sided with Intercity, stating the 1912 Act did non provide for licensing decisions at "the discretion of an executive officer". The Department of Commerce planned to asking a review by the Supreme Courtroom, but the case was rendered moot when Intercity decided to shut down the New York City station. Still, it had raised pregnant questions about the extent of Hoover'southward say-so.[v]

A secord, ultimately successful, challenge occurred in 1926. The Zenith Radio Corporation in late 1925 established a high-powered radio station, WJAZ, with a transmitter site outside Chicago, Illinois. Afterward existence informed that there might not be an available frequency for the station to apply, company president East. F. McDonald proposed that, because they only wanted to broadcast two hours a week, they would be happy with an consignment on 930 kHz that was limited to 10:00 p.m. to midnight Central fourth dimension on Thursday nights, when the only other station on the frequency, KOA in Denver, Colorado, was normally off the air. Despite McDonald's initial expression of satisfaction with a schedule of just two hours per week, his tone before long changed. At this time the U.s. had an breezy agreement with Canada that half-dozen designated AM ring frequencies would exist used exclusively by Canadian stations. In early on January 1926, McDonald directed WJAZ to move from its 930 kHz consignment to 910 kHz, 1 of the restricted Canadian frequencies, and begin expanded hours of operation.[half-dozen]

Invoking the Intercity Radio Company case rulings, Zenith ignored the Commerce Department's order to return WJAZ to its assigned frequency. On Jan xx, 1926, a federal court suit, United States versus Zenith Radio Corporation and E. F. McDonald, was filed in Chicago. McDonald expected a narrow ruling in his favor, claiming that simply a pocket-size number of stations, including WJAZ, held the "Class D Developmental" licenses that were free from normal restrictions. Still, the actual upshot was sweeping. On Apr xvi, 1926, Approximate James H. Wilkerson'south ruling stated that, under the 1912 Human action, the Commerce Department in fact could not limit the number of broadcasting licenses issued, or designate station frequencies. The government reviewed whether to try to appeal this decision, only Acting Chaser General William J. Donovan's analysis concurred with the court's decision.[7]

The immediate result was that, until Congress passed new legislation, the Commerce Department could not limit the number of new broadcasting stations, which were now complimentary to operate on whatsoever frequency and apply any power they wished. Many stations showed restraint, while others took the opportunity to increase powers and move to new frequencies (derisively called "wave jumping"). The extent to which this new environment resulted in disruption for the average listener is difficult to judge, but the term "chaos" started to announced in discussions.[viii]

Federal Radio Commission [edit]

Radio Act of 1927 [edit]

Prior to the early 1926 adverse ruling on the Commerce Department's regulatory authorization, there had been numerous efforts in the U.S. Congress to supplant the Radio Deed of 1912 with a more comprehensive bill, only none of these efforts made much headway. The need for new legislation gained additional importance considering, in the absence of federal regulation, stations were taking their individual disputes to the courts, which began to return decisions favoring incumbent stations. This effectively was granting established stations "property rights" in the utilise of their assignments, which the government wanted to avoid, because it mostly considered the radio spectrum to be a public resource.

Despite the recognition that new legislation was needed, there was a lack of consensus whether it should increment the authority of the Secretary of Commerce, which opponents argued would create a besides-powerful "Radio Czar", or if an independent regulatory trunk was needed, which some disputed was unneeded and overly expansive. The legislation ultimately passed was known equally the Dill-White Beak, which was proposed and sponsored past Senator Clarence Dill (D-Washington) and Representative Wallace H. White Jr. (R-Maine) on December 21, 1926. It was brought to the Senate floor on Jan 28, 1927, and, as a compromise, specified that a five member committee would be given the ability to reorganize radio regulation, just most of its duties would end after one twelvemonth. After a month of debates this bill was passed on Feb 18, 1927, as the Radio Act of 1927,[9] and signed into law by President Calvin Coolidge on February 23, 1927.[10] The Committee's organizational meeting was held on March 15.

Commissioners [edit]

The five regional zones established by the Radio Act of 1927.

The Radio Act of 1927 subdivided the country into five geographical zones, and specified that ane commissioner would exist appointed who resided within each zone. Terms were initially for up to six years, although this was later reduced to 1 year, and no more than three commissioners could be members of the same political party. The FRC's commissioners, by zone, from 1927 to 1934 were:

- Orestes H. Caldwell (New York), (editor of Radio Retailing mag); Caldwell resigned February 23, 1929, and was replaced by Due west. D. L. Starbuck (New York), Patent Chaser, appointed May 1929.

- William H. G. Bullard (Pennsylvania); Bullard died November 24, 1927, and was replaced by Ira E. Robinson (W Virginia), State Supreme Court judge, who resigned January 1932, and was succeeded past the March 28, 1932, appointment of Col. Thad H. Brown (Ohio), lawyer and politico holding various offices including Ohio'south Secretary of State, who served for the residuum of the FRC's being and was appointed to the FCC in 1934.

- Eugene O. Sykes (Mississippi) served the unabridged time the FRC existed and was appointed to the FCC in 1934.

- Henry Adams Bellows (Minnesota); Bellows was forced to resign October 31, 1927, and later became chairman of the National Association of Broadcasters. He was replaced by Sam Pickard (Kansas), who resigned January 31, 1929, and was succeeded by Charles McKinley Saltzman (Iowa), who was appointed May 1929, resigned in June 1932, and was succeeded by James H. Hanley

- John F. Dillon (California); Dillon died Oct 8, 1927, and was replaced by Harold A. Lafount (Utah); Lafount stayed on the FRC until its replacement by the FCC, merely he was non appointed to that torso. In the late 1930s he became president of the National Independent Broadcasters.

The 5 initial appointments, made by President Coolidge on March 2, 1927, were: Admiral William H. 1000. Bullard as chairman, Colonel John F. Dillon, Eugene O. Sykes, Henry A. Bellows, and Orestes H. Caldwell. Bullard, Dillon and Sykes were confirmed on March 4, but activity on Bellows and Caldwell was deferred, so they initially participated without pay. In October 1927 Dillon died and Bellows resigned. During the side by side month Bullard died, and Harold Lafount and Sam Pickard were appointed.[x] It wasn't until March 1928, after Caldwell was approved by a one vote margin and Ira E. Robinson was appointed every bit chairman, that all 5 commissioner posts were filled with confirmed members.

Responsibilities [edit]

To rectify the limitations of the 1912 human action, the FRC was given the power to grant and deny licenses, assign station frequencies and power levels, and event fines for violations. The opening paragraph of the Radio Act of 1927 summarized its objectives as:

"...this Act is intended to regulate all forms of interstate and foreign radio transmissions and communications within the The states, its Territories and possessions; to maintain the control of the U.s. over all the channels of interstate and foreign radio transmission; and to provide for the use of such channels, just non the ownership thereof, by individuals, firms, or corporations, for limited periods of time, under licenses granted past Federal potency, and no such license shall exist construed to create any right, beyond the terms, conditions, and periods of the license."[ix]

Some technical duties remained the responsibleness of the Radio Division of the Section of Commerce, and because Congress failed to provide funding for a staff, during the FRC'due south first twelvemonth the commission was heavily dependent on support from Commerce personnel. Moreover, most of the FRC'south work was expected to be completed within one year, and the original intention was that a majority of its functions would then revert to the Secretary of Commerce:

"Sec 5. From and after one year afterward the first meeting of the committee created by this Act, all the powers and authority vested in the commission under the terms of this Deed, except as to the revocation of licenses, shall be vested in and exercised past the Secretary of Commerce; except that thereafter the committee shall have power and jurisdiction to human action upon and determine any and all matters brought before it under the terms of this section."[9]

Acting as a bank check on the commission's power, "censorship" of station programming was non immune, although extreme language was prohibited:

"Sec. 29. Nothing in this Deed shall be understood or construed to give the licensing authority the ability of censorship over the radio communications or signals transmitted by any radio station, and no regulation or condition shall be promulgated or fixed by the licensing authority which shall interfere with the right of free spoken communication by ways of radio communications. No person within the jurisdiction of the United States shall utter any obscene, indecent, or profane language past means of radio advice."[ix]

However, the "public interest, convenience, or necessity" standard allowed the Commission to take into consideration program content when renewing licenses, and the ability to take abroad a license provided some degree of content command. This immune the FRC to crack down on "vulgar" language — for case the profanity-filled rants of William K. Henderson on KWKH in Shreveport, Louisiana.[11] Only information technology also led to First Subpoena costless speech disputes over the appropriateness of some FRC actions.

A forerunner of the FCC's later "equal-time dominion" required stations to give equal opportunities for political candidates:

"Sec 18. If any licensee shall permit any person who is a legally qualified candidate for any public office to use a broadcasting station, he shall afford equal opportunities to all other such candidates for that office in the apply of such dissemination station, and the licensing dominance shall brand rules and regulations to behave this provision into upshot: Provided, That such licensee shall have no ability of censorship over the material broadcast under the provisions of this paragraph. No obligation is hereby imposed upon whatever licensee to allow the use of its station by any such candidate."[9]

The Radio Human action of 1927 did not qualify the Federal Radio Commission to make any rules regulating advert, although section 19 required advertisers to properly identify themselves.[9] There was virtually no mention of the radio networks — notably the National Broadcasting Visitor (NBC) and, a bit later the Columbia Broadcasting System) (CBS) — that were in the procedure of dominating dissemination, other than a argument in section 3 that "The Committee shall have the authority to make special regulations applicable to stations engaged in chain broadcasting".[9]

In early on 1928 it became clear that the FRC needed more than a single twelvemonth to perform its tasks, and its tenure was extended for an additional year. In December 1929 the commission's mandate was extended indefinitely.[12]

The FRC's regulatory activities, and the public's knowledge of its piece of work, primarily focused on broadcasting stations. Nevertheless, in 1932, in addition to 625 broadcasting stations, the commission oversaw numerous other station classifications, including approximately thirty thousand amateur radio stations, ii thousand send stations, and one thousand stock-still-bespeak land stations. On Feb 25, 1928, Charles Jenkins Laboratories of Washington, DC, became the first holder of a television license.

Selected major FRC deportment [edit]

The most critical result the FRC faced at the fourth dimension of its creation was an excess of broadcasting stations, which now numbered 732, all on the AM band. (The FM broadcast band would not exist created until 1941). There were some significant technical restraints on the number of stations that could operate simultaneously. At night, a alter in the ionosphere allows radio signals, especially from more than powerful stations, to travel hundreds of kilometers. In addition, at this time transmitter frequency stability was oft limited, which meant that stations broadcasting on nominally the same frequency ofttimes were actually slightly offset from each other, which produced piercing loftier-pitched "heterodyne" interference at even greater distances than the mixing of their audio. Another tool that was not however bachelor was directional antennas that could restrict signals to specified directions. Overall, the main tools available for insuring quality reception was limiting the number of stations operating concurrently, which meant restricting some stations to daytime-simply operation, and in many cases requiring time-sharing, where upwards to four stations in a given region had to divide up the hours each used on a unmarried frequency.

General Club 32 [edit]

On May three, 1927, the FRC fabricated the outset of a series of temporary frequency assignments, which served to reassign the stations operating on Canadian frequencies, and too eliminate "split up-frequency" operations that brutal outside of the standard of transmitting on frequencies evenly divided past 10 kHz.[13] The FRC conducted a review and census of the existing stations, then notified them that if they wished to remain on the air they had to file a formal license application by January xv, 1928, as the first step in determining whether they met the new "public interest, convenience, or necessity" standard.[14]

Subsequently reviewing the applications, on May 25, 1928, the FRC issued Full general Club 32, which notified 164 stations that the initial review had found their justification for receiving a license insufficient, and they would have to attend a hearing in Washington, D.C. Moreover, "At this hearing, unless yous tin brand an affirmative showing that public involvement, convenience, or necessity will be served past the granting of your application, it volition exist finally denied."[15]

Many low-powered independent stations were eliminated, although 80-one stations did survive, most with reduced ability. Educational stations fared especially poorly. They were ordinarily required to share frequencies with commercial stations and operate during the daytime, which was considered of limited value for adult pedagogy.

General Order forty [edit]

With the roster of stations now reduced to a somewhat more manageable level, the FRC side by side embarked on a major reorganization of broadcasting station frequency assignments. On August 30, 1928, the Commission issued General Order 40, which divers a "broadcast band" consisting of 96 frequencies from 550 to 1500 kHz. Six frequencies were restricted for exclusive use Canadian stations, leaving ninety bachelor for the slightly fewer than 600 U.S. stations.[16] The new assignments went into effect on November eleven, 1928.[17]

Forty of the available frequencies were reserved for loftier-powered "clear channel" stations, which in nigh cases had simply a single station with an sectional nationwide assignment. Although more often than not accepted equally being successful on a technical level of reducing interference and improving reception, there was also a perception that large companies and their stations had received the all-time assignments. Commissioner Ira E. Robinson publicly dissented, stating that: "Having opposed and voted against the programme and the allocations made thereunder, I deem it unethical and improper to take part in hearings for the modification of same".[18] Some afterwards economic assay has concluded that the early radio regulation policies reflected regulatory capture and rent-seeking.[nineteen]

WGY consignment [edit]

Near of the FRC decisions reviewed past the courts were upheld, still a notable exception involved WGY in Schenectady, New York, a long established high-powered station owned by General Electric. Nether the November 11, 1928, reassignment plan, WGY was limited to daytime hours plus evening hours until sunset in Oakland, California, where KGO, transmitting on the same frequency, was located. Previously, WGY had operated with unlimited hours. On February 25, 1929, the Courtroom of Appeals of the District of Columbia ruled that restricting WGY's hours "was unreasonable and not in the public involvement, convenience or necessity"[20] The U.S. Supreme Court agreed to have the FRC's entreatment, but following oral arguments declined to outcome a ruling, afterwards deciding that under current legislation it did not have oversight, thus allowing the lower court ruling to stand.[21]

KFKB deletion [edit]

KFKB was a popular Milford, Kansas dissemination station, licensed to an organization controlled by John R. Brinkley, known as "The Goat Gland Doctor" due to his promotion of "sexual rejuvenation" surgery that included implantation of slivers of goat testes.

In 1930 the Federal Radio Commission denied his request for renewal, primarily on the grounds that, instead of beingness operated as a public service, the station was primarily beingness run as "a mere offshoot of a particular concern". (In one of Brinkley'south programs he read listener mail describing medical problems, then recommended medication of dubious value, identified by numbers, over the air. Listeners had to visit a Brinkley "boot back" chemist's shop to buy these items.)

Brinkley appealed on the grounds that this was prohibited censorship, simply the U.S. Court of Appeals denied his appeal, stating "This contention is without merit. At that place has been no endeavor on the part of the commission to subject whatsoever function of appellant's broadcasting matter to scrutiny prior to its release. In considering the question whether the public interest, convenience, or necessity will exist served by a renewal of appellant'southward license, the commission has merely exercised its undoubted right to have note of appellant's past conduct, which is not censorship."[22]

Denied this station, Brinkley moved his operations to a serial of powerful Mexican outlets located on the U.S. border, which helped to lead to implementation of the Northward American Regional Broadcasting Agreement in 1941.

KGEF deletion [edit]

KGEF was a broadcasting station first licensed in late 1926 to Trinity Methodist Church building, South, in downtown Los Angeles.[23] Its programming was dominated by long denunciations fabricated past pastor Robert "Fighting Bob" Shuler,[24] who stated that he operated the station in order to "brand information technology hard for the bad human to do incorrect in the community", merely his strident broadcasts soon became very controversial.[11] After a 1931 evaluation of the station'southward renewal application, master examiner Ellis A. Yost expressed misgivings nearly Shuler'south "extremely indiscreet" broadcasts, but recommended blessing.[25] All the same, a review past the Commission concluded that the station should be deleted, because it "...could non determine that the granting thereof was in the public interest; that the programs broadcast past its principal speaker were sensational rather than instructive and in two instances he had been convicted of attempting over the radio to obstruct orderly assistants of public justice".[26]

The Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia affirmed the Commission's determination and held that, despite Get-go Amendment protections: "...this does not hateful that the Government, through agencies established by Congress, may not reject a renewal license to one who has abused it to broadcast defamatory and untrue thing. In that example there is non a deprival of the freedom of speech but merely the application of the regulatory power of Congress in a field inside the scope of its legislative authority".[26] The court besides ruled that denying license renewal equally not in the public interest did non violate the Fifth Subpoena's prohibition of "taking of property" without due process of law.[27] This ruling became final afterward a petition for writ of certiorari requesting review by United states of america Supreme Courtroom was denied.[28]

WNYC assignment [edit]

Under the November eleven, 1928, reorganization, WNYC, the municipal station of New York City, was given a one-half-time, low-power consignment. The station appealed on the grounds that it should have been given a full-time authorization, only lost. Fifty-fifty though the station was government owned, the Federal Radio Commission said that city ownership did not give the station whatever special continuing under the "public interest, convenience, and necessity" standard.[29] However, the instance was viewed equally representative of the preferences given to commercial interests above those of non-commercial stations.

Davis Subpoena implementation [edit]

Section ix of the 1927 Act included a general declaration nearly the need to equitably distribute station assignments, stating: "In considering applications for licenses and renewals of licenses, when and in and then far as there is a demand for the aforementioned, the licensing authorisation shall brand such a distribution of licenses, bands of frequency of wave lengths, periods of fourth dimension for operation, and of power amidst the different States and communities as to give fair, efficient, and equitable radio service to each of the same."[9] The 1928 reauthorization strengthened this mandate, by including a provision, known as the "Davis Amendment" after its sponsor Representative Ewin L. Davis (D-Tennessee), that required "a fair and equitable allotment of licenses, wave lengths, time for operation, and station ability to each of the States, the District of Columbia, the Territories and possessions of the Usa within each zone, according to population".[xxx] This resulted in an additional caste of complexity, for in addition to stations being judged on their individual merits, the committee had to monitor whether in heavily populated areas a decision would cause a zone or state to exceed its calculated quota.

In cases where two or more than stations shared a common frequency on a timesharing basis, a station could petition the FRC to have its hours of operation increased past having the other stations deleted. A prominent example under the FRC'south jurisdiction occurred when a Gary, Indiana station, WJKS, proposed the deletion of its two timeshare partners, WIBO and WPCC, both located in Chicago, Illinois. A major justification was that Indiana was currently nether-quota based on the Davis Subpoena provisions, while Illinois had exceeded its allocation. The commission ruled in favor of WJKS, however the Courtroom of Appeals of the District of Columbia reversed the determination, calling it "arbitrary and capricious". The FRC appealed the lower court decision to the Supreme Courtroom, stating that the issue impacted 116 separate cases awaiting before it.[28]

A unanimous Supreme Courtroom overturned the District Court, and ruled in FRC's favor, upholding the validity of the Davis Subpoena provisions.[31] WIBO made a final attempt to convince the FRC that the expression of potent ties to Indiana by WJKS was fraudulent, and WJKS's owners were actually attempting to establish another Chicago station. This appeal was unsuccessful, and both WIBO and WPCC had to cease broadcasting. In 1934 the Davis Subpoena provisions were carried over to the FCC, but they were repealed on June v, 1936.[32] In 1944 WJKS, later on irresolute its call messages to Wind, moved from Gary to Chicago.

Replacement by the Federal Communications Committee [edit]

The Communications Human action of 1934 abolished the Federal Radio Committee and transferred jurisdiction over radio licensing to the new Federal Communications Committee (FCC). Title Iii of the Communications Act contained provisions very similar to the Radio Human activity of 1927, and the FCC largely took over the operations and precedents of the FRC. The law also transferred jurisdiction over communications common carriers, such as telephone and telegraph companies, from the Interstate Commerce Commission to the FCC.

References [edit]

- ^ Pub.L. 69–632

- ^ "An Act to regulate radio communication", canonical Baronial thirteen, 1912, Radio Communication Laws of the United states of america (July 27, 1914, edition), pages 6-fourteen.

- ^ "Amendments to Regulations", Radio Service Bulletin, January 3, 1922, page x.

- ^ WJAZ "wave pirates" publicity photograph, Popular Radio, May 1926, page 90.

- ^ Intercity Radio Company case, The Law of Radio Communication by Stephen Davis, 1927, page 37.

- ^ The Showtime of Broadcast Regulation in the Twentieth Century by Marvin R. Bensman, 2000, pages 159-160.

- ^ "Federal Regulation of Radio Broadcasting" (July 8, 1926) past Interim Chaser General William J. Donovan, Official Opinions of the Attorneys General of the United States, Book 35, 1929, pages 126-132.

- ^ "Radio Chaos to End Tomorrow Night", Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, Apr 22, 1927, page 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Radio Act of 1927 (Public Law 69-632), February 23, 1927, pages 186-200.

- ^ a b "The Federal Radio Commission" History of Communications-electronics in the United States by Captain Linwood S. Howeth, 1963, pages 505-506.

- ^ a b Freedom of Spoken language by Radio and Idiot box past Elmer E. Smead, 1959, page half-dozen.

- ^ "Iii Years of the Federal Radio Commission" past L. Chiliad. Caldwell, Radio Broadcast, March 1930, pages 270-272.

- ^ "List of broadcasting stations issued temporary permits", Radio Service Bulletin, Apr thirty, 1927, pages 6-xiv.

- ^ "Extension of Broadcasting Station Licenses", Radio Service Bulletin, Dec 31, 1927, page 7.

- ^ "Letter to and list of stations included in General Gild No. 32, issued May 25, 1928", Second Annual Report of the Federal Radio Commission (year ending June xxx, 1928), pages 147-150.

- ^ "General Order No. 40" (August 30, 1928), Radio Service Message, August 31, 1928, pages ix-10.

- ^ "Broadcasting Stations by Moving ridge Lengths, Effective November 11, 1928", Commercial and Authorities Radio Stations of the United States (Edition June 30, 1928), pages 172-176.

- ^ "Commissioner Robinson Stands Firm", Radio Broadcast, January 1929, pages 163-164.

- ^ Hazlett, Thomas W. (May 1997). "Concrete Scarcity, Rent-Seeking and the Outset Amendment". Columbia Law Review. 97 (4): 905. doi:10.2307/1123311. JSTOR 1123311.

- ^ "Litigation" (WGY case), Tertiary Annual Report of the Federal Radio Commission (Covering the catamenia from October one, 1928, to November 1, 1929), folio 72.

- ^ "The WGY Cases", Quaternary Annual Written report of the Federal Radio Commission (For the financial year 1930), pages l-51.

- ^ "The Brinkley Case", 5th Almanac Report of the Federal Radio Committee (Fiscal yr 1931), pages 67-68.

- ^ "New Stations", Radio Service Bulletin, December 31, 1926, page 4.

- ^ Not to be confused with the Robert Schuller of the Crystal Cathedral a generation afterward.

- ^ "Rev. Bob Shuler Wins Radio Plea", Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, August eleven, 1931, Page B-v.

- ^ a b "Trinity Methodist Church Instance", Seventh Annual Written report of the Federal Radio Commission (Fiscal year 1933), page 11.

- ^ "Tertiary Crusader is Taken off the Air", Washington (D.C.) Evening Star, December four, 1932, Office iv, folio 5.

- ^ a b "Government Petitions Supreme Court To Review Ruling in WIBO-WPCC Case", Broadcasting, February 15, 1933, page 28.

- ^ "Litigation" (WNYC), Tertiary Almanac Report of the Federal Radio Commission (Roofing the period from October 1, 1928, to November 1, 1929), pages 73-74.

- ^ "An Act Continuing for 1 year the powers and authority of the Federal Radio Committee under the Radio Act of 1927", approved March 28, 1928, page 2.

- ^ "Readjustments Loom equally WIBO Loses Fight" past Sol Taishoff, Broadcasting, May 15, 1933, pages 5-6, 27.

- ^ "Davis Amendment Repeal Lifts Quota Bar", Broadcasting, June fifteen, 1936, pages 13, 40.

External links [edit]

- The Radio Act of 1927 (text)

- Director of Radio Partition (1929). (1927,1928,1929) Almanac Reports of the Director of Radio Division. United States Department of Commerce Radio Sectionalization.

- Federal Radio Commission Rules and Regulations (U.s.a. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., 1931)

- "The Radio Human activity of 1927 every bit a Product of Progressivism" by Marker Goodman, Media History Monographs, volume 2 (1998-1999) (elon.edu)

- Gorden, Douglas (2002), "Revolutionary Ideas for Radio Regulation", "Section II.A: Long-Run Decline in Administrative Enforcement" (includes citations in impress literature).

- Gorden, Thomas (1990), The Rationality of U.Due south. Regulation of the Circulate Spectrum (discusses the controversy over the FRC and rent-seeking).

What Regulatory Commission Has Control Over T.v. And Radio?,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Federal_Radio_Commission

Posted by: adamsbareiteraw.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Regulatory Commission Has Control Over T.v. And Radio?"

Post a Comment